How Handwashing Became One of Medicine's Most Impactful Innovations

Part 1: On medicine's filthy past and how germ theory convinced doctors that washing their hands was a good idea after all

Fewer people than we'd think wash their hands regularly, or at least when they really should, like after going to the bathroom, or before handling food. It is a sad reality that we have learnt the hard way earlier this decade. I’m not here to shame anyone who sometimes forgets to wash their hands. It happens, I get it. However there is a minority of people who purposefully avoid washing their hands, and they are very vocal about it too.

Among the things that inspired me to write this post there is certainly this video, where a Fox anchorman claims that he hasn't washed his hands in 10 years.

Yuk. This guy says he doesn't believe in germs, because they can't be seen, which is just baffling, given over two centuries of evidence demonstrating their existence.

Germs virtually don't exist on your hands until you:

1. look at them under a microscope

or more likely

2. you go to the bathroom, eat without washing your hands, and you sh*t thyself

This is just to say that even if you don't "believe in germs", germs believe in you. Around half a million deaths every year are attributable to lack of access to hands-washing facilities, people falling sick due to poor hygiene create a huge financial burden. To be honest, it is a bit disheartening that we have to talk about this in 2024, but here we are.

Today we have a pretty good understanding of how and why germs cause diseases, and by that I mean bacteria, yeasts, virus and protozoans. In the second part of this 2-parts series we’ll go full sciency on how these bugs make you sick. We are going to look at what it took to convince doctors of a simple truth: washing your hands can save lives, especially if you are a medical doctor.

As a huge plus, for the audio version of this post we have the pleasure to be joined by fellow Substacker Nicholas, who writes

. Go check his work out if you like brains and the history of medicine!And now, let’s get our hands dirty, and then clean again.

Prologue: I went to the hospital with a broken arm, now I have cholera

Imagine you live in a world where it's your doctor, not a random TV man, who doesn't believe in germs. You go to the hospital with a non life-threatening condition, for example a fracture, and as soon as you step into the hospital, your likelihood of dying skyrocket. The exact rate of mortality in the pre-germ theory and pre-antibiotic eras is pretty hard to estimate accurately. This is due to a variety of different reasons that include the poor record-keeping of hospitals back in the days and the utter lack of valid statistical methods until the 1900s. What we do know however is that surgery has been incredibly deadly until sanitation was introduced as a standard practice in medicine.

Starting from the Middle Ages, surgery and medicine were pretty much two separate things. Treating fractures and wounds and draining abscesses were considered too lowly to be handled by doctors, and were often performed by barbers instead. Even as surgery started to become integrated in the medical practice later on, the number of surgical operations performed remained incredibly low compared to nowadays standard. This was mainly due to the fact that given its staggering mortality rate, surgery was considered a last resort.

One man, Joseph Lister, whom you might know from the mouthwash Listerine™ , changed everything by introducing sanitation. Pioneering what we now know as translational medicine, Lister saw a connection between Pasteur’s new germ theory and the staggering mortality associated with surgery. But let’s go with order.

The rise of causation in medicine

For centuries, medicine did not care about looking within the body for the specific causes of diseases. Starting with Hippocrates and throughout all the middle ages, it was believed that disease were caused by a general imbalance of fluids and material within the body.

Today’s guest for the audio version of this post has written at least a beautiful piece on some good medieval medicine [In today’s post audio version you can hear him himself talking about this stuff!]

Leaving humors and bile aside, fast forward to the 18th century. In 1761 Giovanni Battista Morgagni, an Italian doctor, published De Sedibus et causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis, translated to On the Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy. In this book Morgagni reported his observations gathered during the post-mortem examination of nearly 700 patients, with the aim of understanding the differences that were brought about by diseases on the human body. He wanted to trace back what organ or organs were damaged by diseases and in what way, to then use this knowledge to improve the diagnosis and treatment of (live) patients affected by the same disease. From a modern point of view this sounds almost obvious, but back then it was revolutionary.

The novelty brought by Morgagni’s approach was not dissecting dead bodies per se though. Dissecting corpses for didactic purposes was a well-established practice, and there are also accounts of doctors antecedent to Morgagni performing what we may call autopsies —investigating the causes of one's death by dissecting and observing their body. However with Morgagni the practice of autopsy reaches its maturity, and very importantly it becomes a tool used in a new discipline, called pathological anatomy or pathology. To pathology we owe standard practices in medicine such as inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. We can also draw a direct line between the birth of pathology and the development of a huge portion of modern molecular medicine, i.e. biochemistry, cell biology etc.

Pathology was soon to be adopted in both in America and Europe. Vienna in particular, became a world-leading center for the study of pathological anatomy. Doctor Karl Von Rokitansky, devoted his career to study thousands of autopsies, looking for patterns and classifying diseases , so much that he was described by a colleague as "the Linnaeus of pathological anatomy". What matters at this point, is that thanks to this new approach medicine moved closer to have a mechanistic understanding of disease, which although coarse improved the quality of diagnostics and treatment of diseases massively.

There was still one piece of the puzzle that was missing before modern medicine could take off on the wings of causality.

Actionable ideas

In 1823 the Allgemeisen Krankenhaus, the hospital where Rokitansky worked, was entrusted to the direction of Johann Klein (in English Small John). Soon after his appointment Tiny John reinstated the rule according to which students were required to learn how to perform obstetric examinations using corpses. In 1834 he opened a new division in the hospital where only midwives and midwifery female students were allowed to practice, while male doctors and medicine students would continue practicing in the first one. The same number of births took place in both divisions every year, between 3000 and 3500, with one striking difference: while no more than 60 patients succumbed every year in the second division, with a mortality of around 2-3%, in the first division 600 to 800 women died every year, around 10 times as much as the second division.

The culprit was a mysterious disease known as puerperal fever, or childbed fever. At the time the causes were attributed to a variety of weird reasons, to name a few: spoiling of breastmilk, retention of feces due to wearing tight clothes, standing up too quickly after delivering, cosmic telluric influences, and a not better specified "bad air" or miasmas. In 1846, after 500 women had already died of childbed fever that year, the government appointed a committee to investigate on the matter, with no success. In that occasion Johnny Shortstack (yes, it’s still Johann Klein, klein means “small” in German) rather than taking any accountability, introduced some pretty random rules such as the mandate for women to give birth while laying on their side, and blamed the insanely high mortality on a miasmas that hoovered over the city and on the bad quality of the walls. They were clueless, and young mothers and mothers-to-be kept dying like flies.

Only one year after in 1847, a young and like myself prematurely bald doctor from Hungary was hired as Tiny John's assistant, his name was Ignas Semmelweis. Semmelweis had started to study law when he was asked to accompany a friend to a pathological anatomy lecture. He later recalled to have immediately fell in love with the subject, and he decided to become a doctor. Since his passion was pathological anatomy, the Allgemeise Krankenhaus was the place to go.

When he started to work as Klein’s assistant, he developed an obsession with puerperal fever. He wanted to not only understand the causes of the disease, but also how to cure it. Of course, in that century Vienna was absolutely not the only place where childbed fever was a problem, and Semmelweis was surely not the first one to have attempted putting an end to it.

In 1795, the Scottish doctor Alexander Gordon wrote:

That the cause of this disease was a specific contagion, or infection, I have unquestionable proof. [...]

When the Puerperal Fever is frequent and fatal, that is, when it prevails as an epidemic, its cause has been referred to a noxious constitution of the atmosphere. [...]

But this disease seized such women only, as were visited, or delivered, by a practitioner, or taken care of by a nurse, who had previously attended patients affected with the disease. [...]

With respect to the physical qualities of the infection, I have not been able to make any discovery; but I had evident proofs that every person, who had been with a patient in the Puerperal Fever, became charged with an atmosphere of infection, which was communicated to every pregnant woman, who happened to come within its sphere.

Gordon argues that if the disease was caused by a generalized atmospheric influence, it should affect all women equally, which was not the case, as he notices. He then proceeds to recommend the use of fire and smoke to prevent the spread of the disease, inviting doctors and nurses that had been in contact with childbed fever patients to wash themselves carefully.

“"The patient’s apparel and bed-clothes ought, either to be burnt, or thoroughly purified; and the nurses and physicians, who have attended patients affected with the Puerperal Fever, ought carefully to wash themselves, and to get their apparel properly fumigated, before it be put on again.”

Similar recommendations will be given in 1843 by Oliver Wendel Holmes. In his essay "On the contagiousness of puerperal fever" he comes to basically the same conclusions as Gordon. Like Gordon, he admits his ignorance when it comes to the specific mode of transmission of the disease, but presents an extensive account of cases from which it becomes evident that doctors where somehow infecting patients with the disease. In giving some indications on how to prevent contagion, Holmes also stresses how important it is for doctors to not visit healthy patients after taking part in post-mortem examinations or after assisting patients sick with puerperal fever.

What's really interesting to me is that neither Gordon nor Holmes have the slightest clue one how the disease is transmitted, and they were very open about it. What they had noticed and extensively documented is essentially that patients of doctors who have been in contact with women ill with puerperal fever were much more likely to get sick.

Opposite to all the conjectures involving miasmas and cosmic influences, this idea is actionable, and it can be used to make testable predictions. For example, Gordon was able to predict with good accuracy which patients were going to get sick based on the doctors and nurses that assisted them. Similarly, washing hands and disinfecting clothes turned out to work, even though the mechanism underlying the how was not understood.

Even among the voices that opposed the "theory of infection" some were willing to compromise for the sake of their patient's health. For example Charles Delucena Meigs, author of Woman: her diseases and remedies, where he essentially argues against the idea of puerperal fever being transmissible, writes:

“Despite my absolute insistence on this disbelief, I am unable to openly challenge the assertions, opinions, and feelings of many of my fellow physicians, who are worthy of my utmost respect; so much so that, in reality, I do not feel free to disobey their strict recommendations to take all necessary precautions to prevent the spread, through myself, of a disease of such a fatal nature

The savior(s) of mothers

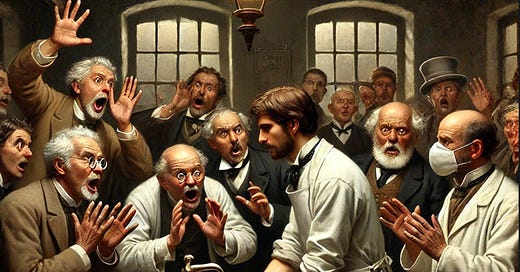

Going back to Semmelweis, he also made similar observations to Gordon and Holmes. He intuited that the difference in mortality between the two divisions at the Allgemeise Krankenhaus could not be due to chance. Sadly, the final piece of evidence, that was standing between him and the greatest breakthrough in his career, came in the form of a tragedy.

His friend and colleague Jakob Kolletschka was performing a forensic autopsy, when he got accidentally injured by a clumsy student, who cut him on a finger with a lancet. Kolletschka succumbed to sepsis days after the incident, so that Semmelweis could finally crack the problem of puerperal fever. When his body was examined post-mortem, Semmelweis himself noticed that his friend’s body had alterations similar to those observed in the bodies of women who had died of puerperal fever.

“It immediately became clear to me that puerperal fever, the fatal disease affecting mothers, and Professor Kolletschka’s illness were exactly the same, as all cases exhibited the same anatomical changes from a pathological perspective. Therefore, if Professor Kolletschka’s sepsis resulted from the inoculation of cadaveric particles, then puerperal fever must originate from the same source. Now, it was only necessary to determine where and how, in cases of childbirth, particles from a decomposing corpse were introduced. The important thing was that the source of transmission of those cadaveric particles lay on the hands of the students and attending physicians.”

Eureka.

In the first division of the Allgemeisen Krankenhaus it was common practice for doctors to visit pregnant women and assist childbirth right after performing autopsies. Semmelweis understood that something was being transmitted from the corpses of patients deceased to puerperal fever to healthy patients. Small injuries that normally took place during childbirth gave the “cadaveric particles“ a perfect entry site into the women’s body, allowing the infection to spread.

In May 1847 Semmelweis convinced the hospital to instate a new rule: doctors and students had to wash their hands in a bowl of a chlorine solution, later replaced with the less expensive calcium hypochlorite, before attending to women in labor. The mortality in the first division plummeted to ~3%, and in a year it was pretty much the same as the second division. The introduction of simple handwashing rules spared the lives of >500 women every year, for which Semmelweis will be remembered after his death as the savior of mothers.

Semmelweis is sometimes depicted more as a lonely hero against insurmountable forces than he really was. Starting from Rokitansky himself, doctors and academics of the generation to which Semmelweis belonged to were often in open contrast to the reactionary forces which embodied by Johann Klein, and would often fiercely take Semmelweis’ side. However, his own refusal to publish his own findings until much later in his life did not certainly make his own and his supporters’ lives easy.

Semmelweis’ theory remained misunderstood by his contemporaries, and the rules he had instated were lifted after the left the Allgemeisen Krankenhaus. He began working in a public hospital in his hometown, Pest (nowadays Budapest), and was later appointed professor. In his new workplace Semmelweis was seen as an outsider in his own country, and wasn’t listened to when he tried to replicate the success he had at the Allgemeisen Krankenhaus. The savior of mother suffered from a debilitating decline in mental capacities and was institutionalized in a psychiatric facility. He died after a very short time from his admission, according to some due to beatings inflicted by the psychiatric ward’s personnel.

The father of sanitation: Joseph Lister

Similar to Semmelweis, the English surgeon Joseph Lister was not convinced by the popular concept of miasma. When he started working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, between 45% and 50% of his amputation cases would die from sepsis. He was convinced that some kind of substance was to be blamed for the infection, but like Semmelweis and his predecessors, was clueless about the what, exactly.

Around the same time, the well known French chemist Luis Pasteur had already disproven the theory of spontaneous generation of life. Before Pasteur’s ground-breaking work it was believed that life could spontaneously arise if the right conditions were met, and that organic matter was available to be decomposed. When several winemakers around France started to report substantial losses due to batches of wine the by all appearances spontaneously spoilt, Napoleon III commissioned Pasteur with investigating on the matter. He found that the presence of microbes in the wine was predictive of the wine going bad, and proposed to heat the wine to kill the germs responsible for the spoilage of wine. The method became later known as pasteurization.

Lister must have thought something silly like “if these microbes can get wine sick, why wouldn’t the same thing make people sick too?”, or with his own words:

"Turning now to the question how the atmosphere produces decomposition of organic substances, we find that a flood of light has been thrown upon this most important subject by the philosophic researches of M. Pasteur, who has demonstrated by thoroughly convincing evidence that it is not to its oxygen or to any of its gaseous constituents that the air owes this property, but to minute particles suspended in it, which are the germs of various low forms of life, long since revealed by the microscope, and regarded as merely accidental concomitants of putrescence, but now shown by Pasteur to be its essential cause, resolving the complex organic compounds into substances of simpler chemical constitution"

(Lister, J., 1867 “ON A NEW METHOD OF TREATING COMPOUND FRACTURE, ABSCESS, ETC.: WITH OBSERVATIONS ON THE CONDITIONS OF SUPPURATION”)

Interestingly, the observation of microbes by means of microscopy had been made possible not too long before Lister became a surgeon. Chromatic aberration had affected microscopy since its beginning, and made it practically impossible to observe something as small as a microbe under a microscope. The problem was eventually cracked by a medical doctor with the passion for microscopy, Joseph Jackson Lister, the father of the Lister in our story. How wholesome.

Like Semmelweis, Lister insisted for new sanitation rules to be introduced in the hospital where he worked. Surgeons and nurses had to disinfect their hands with a solution containing phenol (known as carbolic acid back then) before surgical operations. The same solution was used to disinfect instruments and rooms themselves, using a large spray tank affectionately called the “donkey engine”. Again, it was a massive hit. Mortality associated with surgery dropped from 45% to 15% in the Male Accident ward where lister worked.

Expectedly, Lister encountered some resistance. However, without going too much into the details of his later career, it’s important to note that differently from Semmelweis, Lister saw his theory pretty much universally accepted within the medical community during his lifetime. This is likely due to Lister’s undoubtedly better PR skills compared to Semmelweis’, but I will argue that there is more to that.

There is no cure for a bruised ego

The question comes by itself: why were doctors so reluctant to integrate this new practice into their work?

It's worth noting at this point that the appointment of Johann Klein as director of the Algemeisen Krankenhaus was the result of a direct decision issued by the imperial government. Given the period of political agitation in Europe, someone like Small John, conservative and loyal to the imperial authority, was part of a larger strategy to keep a tight control over the academic world. Semmelweis was openly an Hungarian patriot, and took part to the 1848 political agitations, which put him in blatant contrast to the hospital’s management.

Besides, some of Semmelweis’ opponents had fair concerns about the scientific validity of his work. For example, the Danish doctor Carl Edvard Marius Levy suggested that if doctors and students were responsible for spreading the diseases, temporarily suspending autopsies should have also had a positive effect. He criticized Semmelweis for not having attempted such experiments, and for not having clarified the exact conditions under which infections occurred, for example, if it was only corpses of women that contained the “seed” of the disease.

On the other hand, the quality of records-keeping at the Austrian hospital was commendable, and there was plenty of evidence supporting the efficacy of Semmelweis’ hygiene rules. At the same time, no supporting evidence was ever produced which showed that miasmas were the cause of puerperal fever, and none of the speculations concerning the cause of the epidemic had lead any closer to getting less people sick.

From the perspective of a 19th-century physician, suggesting that doctors themselves were the responsible of spreading of puerperal fever was nothing short of a devastating accusation. It implied that they bore direct responsibility for the sudden deaths of hundreds of mothers. Such an insinuation would not only tarnish their professional reputation but also confront them with the harrowing possibility that their well-intentioned actions had caused unimaginable suffering.

Either because of their ability at self-deception, or because their inability to understand what Semmelweis had unveiled, these feelings were certainly not shared by those members of the medical establishment who opposed the new theory. Those who instead were willing to consider the possibility of having caused suffering due to their ignorance had a much harder time. The case of Gustav Adolf Michaelis is quite telling in this sense. He had personally assisted his niece during childbirth, which tragically ended with her dying of puerperal fever. After introducing sanitation in his clinic and witnessing the dramatic drop in mortality rates the resulted from it, Michaelis was devastated by the realization that his beloved niece’s death could have been prevented. That was a blow he would not recover from. Crushed by guilt and remorse, Michaelis took his own life.

It seems to me that the introduction of the concept of germs shifted the blame away from the doctors themselves. Semmelweis’ and others’ appeal to generic “particles” was evidently not enough for this shift of prospective to take place, but after the existence of germs was proven, it provided a scapegoat onto which doctors could project agency. While Semmelweis was correct in identifying that doctors were unknowingly carrying 'something' harmful, it’s understandable how his colleagues might have interpreted this as a personal accusation of uncleanliness. with germs, handwashing and sanitation went from being seen as an admission of poor hygiene into an act of combating an invisible foe.

Dear germs deniers, please wash your hands

Would you be comfortable being operated by a surgeon who hasn’t washed their hands prior? I doubt that, because in the end, we are all used to the safety that observing basic hygiene rules provides. There is a concerning number of people who, for several reasons, don’t believe in germs. I know some of them, and few of them are my friends too. Just to be clear, none of them would reply with a ‘yes’ to the question above, because they like to be alive.

If we have learnt anything at all is that people who are not convinced by the existence of germs have on them the burden of providing a better explanation for where communicable diseases come from and how to prevent them from spreading. Historically, every other alternative explanation has always failed.

Washing your hands regularly, especially after going to the bathroom and after being in crowded places like the subway, is a small action that protects you and the people around you.

Besides, have you ever spat on a Petri dish…? Here’s some evidence, you can do it yourself at home.

Thank you so much for reading!

Sources

"Autopsy | History, Procedure, Purposes, & Facts." Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/autopsy.

Carter, K. C. “The Development of Pasteur’s Concept of Disease Causation and the Emergence of Specific Causes in Nineteenth-Century Medicine.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 1991, 65 (4), 528–548.

"Deaths Attributable to Lack of Access to Handwashing Facilities." Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/deaths-due-to-lack-of-access-to-hand-washing-facilities?tab=chart&country=~OWID_EUR.

"Ignaz Semmelweis | Biography & Facts." Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ignaz-Semmelweis.

"Ignaz Semmelweis: A Victim of Harassment?" Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10354-020-00738-1.

Iezzoni, L. I. “100 Apples Divided by 15 Red Herrings: A Cautionary Tale from the Mid-19th Century on Comparing Hospital Mortality Rates.” Ann Intern Med 1996, 124 (12), 1079–1085. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-124-12-199606150-00009.

"Latest Research Shows Improvement in Aussie Handwashing - But Blokes Still Need to Do Better!" Food Safety Australia. https://www.foodsafety.asn.au/topic/latest-research-shows-improvement-in-aussie-handwashing-but-blokes-still-need-to-do-better-global-handwashing-day-15-october-2023/.

Lehrer, S. Explorers of the Body: Dramatic Breakthroughs in Medicine from Ancient Times to Modern Science. 2006.

Levy, Carl Edvard Marius. “De nyeste Forsøg i Fødselsstiftelsen i Wien til Oplysning om Barselfeberens Ætiologie.” Danish Wikisource. https://da.wikisource.org/wiki/De_nyeste_Fors%C3%B6g_i_F%C3%B6dselsstiftelsen_i_Wien_til_Oplysning_om_Barselfeberens_%C3%86tiologie.

Morgagni, G. B. On the Seats and Causes of Diseases as Investigated by Anatomy. https://www.britannica.com/topic/On-the-Seats-and-Causes-of-Diseases-as-Investigated-by-Anatomy.

Nuland, Sherwin B. The Doctor’s Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis.

Perini Journal. "The Savior of Mothers." http://www.perinijournal.it/Items/en-US/Articoli/PJL-42/The-savior-of-mothers.

Rosen, G. A History of Public Health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

Rothstein, William G. Public Health and the Risk Factor: A History of an Uneven Medical Revolution. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/publichealthrisk0000roth.

Science and Society, Volume 16. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sciencesociety160000unse/page/n5/mode/2up.

"State of the World’s Hand Hygiene." UNICEF. https://data.unicef.org/resources/state-of-the-worlds-hand-hygiene/.

"Study Reveals Hand-Washing Habits of Europeans." Jakub Marian. https://jakubmarian.com/a-study-reveals-how-many-europeans-wash-their-hands-with-soap/.

"The Dirty History of Doctors’ Hands." Popular Science. https://www.popsci.com/health/germ-theory-terrain-theory/.

"The Effect of Handwashing with Water or Soap on Bacterial Contamination of Hands." PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3037063/.

"World Hand Hygiene Day: Insights From the 2024 Healthy Handwashing Habits Survey." Infection Control Today. https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/world-hand-hygiene-day-insights-2024-healthy-handwashing-habits-survey.